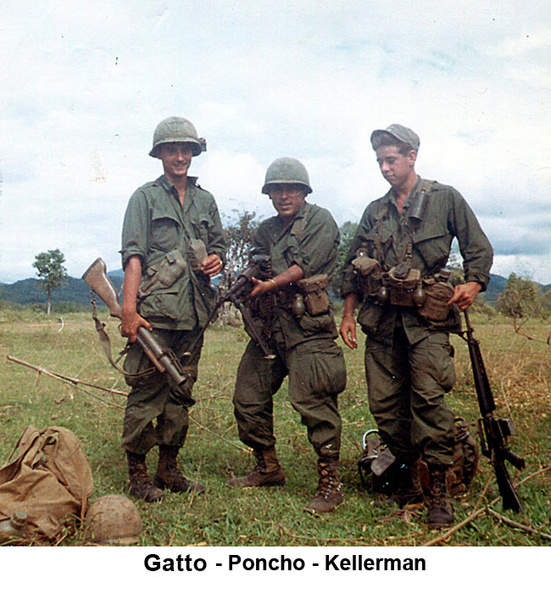

By Tabitha Evans Moore | EDITOR & PUBLISHER

The first time Army combat vet Phil Gatto watched someone die in Vietnam, it happened unexpectedly and to someone who’d momentarily let their guard down. War works that way. It doesn’t play by the rules. There is no script.

After humping up and down a mountain region located near Tuy Hua – a town located beside the South China Sea – Gatto, who’d arrived in Vietnam only days earlier, found himself in the rear of a unit chasing a North Vietnamese Army (NVA ) regiment through the mountain without an extra pair of socks.

“I forgot to pack an extra pair of socks in my rucksack and my feet got covered with sores and blisters. I was eventually sent to the rear area with a bad case of immersion foot,” he says. “A guy who was, like me, on light duty overseeing Vietnamese workers in the mess tents, was looking at the mail he’d just received and was standing next to a trash barrel when it exploded – killing him instantly. Apparently, some VC had put a mortar round into the burn barrel.”

“I wanted to be a real soldier.”

Though Gatto is “officially” a native of Chicago, he’s lived in Tennessee since he was a very young child. His father, Frank Gatto, arrived early at Camp Forrest in nearby Tullahoma. There, Frank met Phil’s mother, Nell Mitchell, of Gattistown.

Gatto grew up in Tullahoma and graduated from Tullahoma High School in 1965 and attended Tennessee Tech before enlisting in the United States Army. While in the Army, he met Glenda Davison at church and in school. The couple live in Moore County near the Cobb Hollow area.

“We have been blessed with two daughters, Angie Maxey and Tiffany Bryson, both graduates of Moore County High School and Middle Tennessee State University. Angie is married to Danny Maxey of Tullahoma, and they have four children, Faith Simpson, Josh Deckelman, Maddi Maxey and Tyler Maxey. Tiffany married David Bryson of Tullahoma and they have five children: Riley, Eli, Matt, Eme, and Trevor. My granddaughter Faith is married to Aidan Simpson and they have two children, Bella and Luca, who also live in Lynchburg.”

Gatto enlisted in the Army while attending Tennessee Tech in 1966 though he’d originally planned to be a U.S. Marine.

“Their recruiter was out of town the day I signed up,” he says.

He arrived in Vietnam in September 1966 as just another private at the 90th Replacement Depot at Long Binh, which he describes as a dusty hill covered with general purpose tents. When he first arrived, Gatto says a finance officer spotted his business major status, and offered him a desk job – one he refused.

“I told him I wanted to be a real soldier rather than a bookkeeper,” Gatto says. “I remember him smiling and shaking his head kind of sad-like.”

He’d only been there two days, when the storied 101st Airborne offered him a spot.

For those that don’t know, the 101st gained instant fame for its role in D-Day (Normandy) and the Battle of the Bulge (Bastogne) during World War II. They’re a gritty, disciplined division that’s earned a reputation as one of the most elite in the U.S. Army. They are headquartered at Fort Campbell, which straddles the Tennessee-Kentucky border, just northwest of Nashville.

The 101st arrived in Vietnam in 1967, where it remained active until 1972 – transitioning from an airborne role to airmobile, utilizing helicopters for rapid deployment and combat—becoming “The Air Assault Division” we know today.

“Once I got to Charlie Company they were located beside the South China Sea at a town named Tuy Hua,” Gatto says. “I was a bit intimidated by becoming a part of such a heroic group, but they welcomed me to the company pretty quick.”

Gatto eventually became a member of the “Crispy Critters” – a slang name soldiers used to describe the use of napalm to defend their positions. Gatto would eventually learn that overwhelming NVA attacks forced his very own Captain Carpenter to call napalm strikes on his own lines during a huge battle at Dak To. It’s one of those kill or be killed moments that happen in war. Something you can only understand, if you’ve seen it with your own eyes.

Until 1967, Gatto says officials used the 1st Brigade as fire and rescue service in Vietnam.

“It was a perfect example of what warfare has been described by other generations: long periods of drudgery and boredom, interspersed with moments of intense excitement and terror,” he says. “But by the earlier part of 1967, there was a major increase in the excitement and terror.”

Gatto says that’s when deployed soldiers started to notice the photos of student protests happening in the U.S. New arrivals would tell horror stories about how your uniform could get you attacked in airports or on the street.

What had started as “civil rights” protests and freedom rides eventually escalated major anti war marches in Washington, D.C. and major college campuses across the U.S. By 1968, it all came to a boil when the Tet Offensive shocked Americans by revealing that the war was far from won – contradicting government claims.

Their vitriol towards soldiers became clear the day Gatto and his unit discovered a medical supplies cache in a cave with a note that it had been sent by their “Peace Loving Supporters at the University of California in Berkeley.”

“We were a unit composed, more or less, of volunteers, you don’t get drafted into the Airborne. Most of us had fathers who served their country in a World War, and who taught us that as a superpower, America, would have to help the weaker nations, who were friends against the Communist,” Gatto explains.

“The government told our fathers that Communists wanted to inflict their ideology onto the rest of the world. They were telling us what our government had told them, and what the talking heads on TV and in the magazines and newspapers had told them, and us, over the years. Apparently, somebody had lied.”

Gatto says the student protests were a tipping point in which things quickly fell apart in Vietnam for those risking life and limb to accomplish something that rang less and less true with each passing day. He says he watched “so-called journalist” recording “fire fights” – that were actually only weapons being zeroed-in or being test fired – in helmets and flak jackets that the Army couldn’t afford to give its frontline soldiers.

“A glance at the Stars & Stripes presented the military’s own line of BS to troops who knew better,” Gatto says. “And then, there were the career politicians back home – the same group who were really responsible for the whole heart-breaking mess – men and women more committed to being re-elected than to actually accomplishing anything for their country’s citizens.”

“It’s too bad they didn’t kill you.”

Gatto says it all caught up to him one dark night beside a creek in the mountains near Duc Pho. There, during the “excitement and terror” an artillery round took off his left foot and significantly damaged his lower right leg as well.

“Other soldiers risked their lives and limbs to get me to a helicopter and its crew risked their lives to get me to an aid station. After surgeries and stops in the Philippines, Japan, and finally, Walter Reed Medical Center, my war ended,” Gatto says.

Or so he thought. While making his way through what is now Reagan Airport in Washington, D.C., Gatto drudged along on crutches in his dress uniform – the left trouser pinned up where a leg once supported him – a sharply dressed woman with a young son approached and asked if he’d been wounded in Vietnam.

Ever the southern gentleman, Gatto replied, “yes ma’am” – very aware of the young, impressionable eyes upon him.

“Too bad,” the woman replied – looking Gatto square in the eyes. “It’s too bad they didn’t kill you.”

Gatto says he remembers being completely taken aback but still very aware of the little boy – wondering if he would be a soldier when his generation’s war happened.

“Yes, ma’am,” he answered. “I think the same thing myself at times. I’d be in a lot better company, I’m thinking.”

“War is destructive and wasteful.”

Looking back, he says that interaction in the airport shouldn’t have been a surprise. His dad tried to warn him.

“Right before I left for Vietnam, my father told me that all the ribbons and badges on my uniform were things that I had earned and that he was proud of me for doing so. Then he told me that, in fact, the more decorative the uniform, the more dirt and filth and regret and sadness each medal and new badge would require,” Gatto says. “He said that I should expect to do and see things done that I would have never imagined doing or seeing. War is destructive and wasteful, and it affects everyone it touches. So I think his talk helped me to deal with my part in the Vietnam War.”

Gatto says he’s moved on from the insults and bigotry that surrounded Vietnam. Looking back, he’s not sure Vietnam served in the best interest of the U.S., but that he’s proud to have served with the men he met there.

“We believed, when we were sent there, that we were doing our country’s will and that we were trying to help a smaller country that was an ally of ours to maintain its republic – just as we’d sworn to protect our own,” Gatto explains. “I think about them just about every day. I especially think about the ones that never made it home; the ones who will be forever 19 years-old in my mind, and in the minds of those who loved them.

It’s not just cliche to state that poor kids die in a rich man’s war. Military service is often the only way out of poverty for too many. The idea that young men from lower-income brackets were disproportionately sent to fight and die in Vietnam is supported by both data and historical analysis. While those in college or graduate schools were handed out deferments, working class kids faced the draft.

It’s something Gatto says he thinks about.

“I’ve always thought that it might be good for the United States to require its citizens to serve two years in some form of national service, immediately after they leave high school, primarily in the armed forces or other branches of federal service. I think it could help young people to mature in a more disciplined way and have an idea of what it is like to be part of something much bigger than yourself,” he says. “Who knows? Maybe we could learn at a much younger age that it is okay to have differences of opinion and that if we take time to think about and discuss it, we might learn something from each other rather than thinking: I’m right, and you never will be.”

Gatto will speak at the Memorial Day Service held on the Lynchburg Square at 11 a.m. on Monday. He’s happy to share his story with others, but really, he’d just like to take the day to sit on his back porch and think about the soldiers who will forever be 19 in his mind’s eye.

“I like to think about what it might have been like to visit Ray Turner and his wife and sisters in Miami, or spend a soft spring day with Rodney and Wymon Evans and their wives in Florala, Alabama. I could have continued to insult Alabama football while having to listen to his jabs about the Volunteers.”

Though he’s been candid with us, talking about war and its effects isn’t his favorite thing to do, though he understands the importance of the truth being told. To that end, he’s decided to mark this Memorial Day by donating a two-volume book, Strike Force: 2/502nd 101st Airborne Division-Vietnam to the Moore County Library.

“The book was written by those of us who served in that unit from 1965-1968. It has maps and photos but best of all, it has the memories – good or bad – of the men who served there,” he says. •

{The Lynchburg Times is a non-partisan, locally owned community newspaper located in Lynchburg, Tennessee. We publish new stories daily as well as breaking news as it happens. It’s run by a Moore County native and Tulane University-educated journalist with over 20 years of experience. It’s also one of the few women-owned newspapers in the state. We are supported by both readers and community partners who believe in independent journalism for the common good. You can support us by clicking here. }